The aged women likewise, that they be in behavior as becometh holiness, not false accusers, not given to much wine, teachers of good things ~ Titus 2:3

"You may forget but let me tell you this: someone in some future time will think of us" ~ Sappho

I needed more money.

That is why I was awake and driving Cab 265. I struggled each week to pay my lease which I did by Friday night. If I had not, they would have cut off my radio and I would get no more rides until I drove up to Bellflower and paid them in cash. Just when I needed money, they could cut off my means to make money. But that week I paid the lease on time.

Saturday and Sunday then, were my only days for profit before the lease clock started again Monday morning. To make the best of it, I would live in the cab for about 48 hours. So that Sunday morning in spring, 1988, I was hoping for a nice fare to the airport or to the Naval base as I drove my cab to 4911 East 2nd Street in Belmont Shores. My cab was still clean from the night before. In fact, I was the smelliest thing in it, having slept several hours in the front seat after the last intoxicants were delivered safely by 4 a.m. I was tired, but the cold and sunny spring morning revived me. The sun felt like optimism, like phone calls from new girls, who I chased relentlessly. But I was about to be the second smelliest thing in that cab.

The fare’s address was not a bar, but a restaurant called Clearman’s Northwoods Inn, famous for its fake snowy roof and icicles. It was too early for any steakhouses to be open, so I thought it odd. Odd it turned out to be. (There are still a few Northwood Inns around, by the way.)

A managerial looking fellow in front of the restaurant waved at me as my yellow Ford Crown Victoria slowly passed eastbound and made a U-turn around the island. He wasn’t smiling and turned away as I stopped at the curb. He reached behind a shrubbery and pulled out a short, elderly woman, swaying and pale. She wore two, maybe three, grey hooded sweat jackets and men’s black trousers. I think she may have had a second pair of pants on underneath. She wore no make-up and her salt-and-pepper bobbed hair was decorated with brown boxwood leaves.

“You get her the fug outta here!” He gripped her right tricep like a vice and her mouth yawned in a silent scream. He tossed her like a bag of rags across the back seat of the car, skidding to the other side, hitting her grey head on the door. The knock broke her silence, a mournful and grating “ouwww” of pain and indignity. It pissed me off; both his cruelty, and her cry.

“Hey, dude, take it easy or I will call the cops,” Which I could do on the taxi’s radio.

“Look, she slept here all night and puked in the doorway.” He turned away saying, “I’m sick of this shit.”

Not a second later her smell hit me. It wasn’t only puke, I can handle puke. This smell was a melange of death, a diabolical swirl of gin fumes, cigarettes, unwashed skin and urine from a bladder that had given up its last full measure of devotion. I had a moment of empathy for that manager. He could not abide a stinking derelict laying in the entrance of his restaurant about to open for Sunday brunch.

I had driven a cab long enough to know that a drunkard tossed into a cab will NEVER have any money. They drink until the money is gone, period. I put all four windows down and turned to her. “Ma’am, You have to tell me where you want to go. If you don’t have money, I will drop you off somewhere close.”

She pushed herself up with her left arm. “I want to go home.”

“And where is that, ma’am?” I said, trying to be civil.

“Just drive and I wee-ill te-well you.” She slurred.

I wasn’t going to do that. But I also knew the ride could be my only fare that Sunday morning. “No, ma’am, you have be specific.”

“San Pedro. Go to San Peder-oh.”

I looked her over carefully; no purse, no bulging pockets. “And how will you pay me?”

“I we-ill give you a check when I get there. I have money.”

I am still not sure not why I caved in, but I think it was the haircut. I would have dropped her off at a bus stop had it not been for that perfectly bobbed haircut. Derelicts don’t get haircuts. It was her one vanity, the one outward sign that she lived for something other than booze. I also needed the money and Belmont to San Pedro was a good fare. Taxi drives depend more on other people’s vices than their virtues. Temperance and Prudence rarely find themselves in a cab. Her vice would help pay my bills and buy me my own booze. I would take the risk.

So I dropped the flag* and we drove west on 2nd Street all the way through Long Beach, past the harbor and Naval yard and over the Vincent Thomas Bridge. I paid the toll, of course.

She remained listless and quiet, her fumes still circulating despite the cool ocean air. Her silence bothered me and I started to worry again. Would she rip me off and waste my time while doing it?

“Ma’am, we are coming into San Pedro. Where to?”

“Just keep going.”

“Ma’am, you said San Pedro. Do you know where you live?”

“Yes, I do. It is just a ways up in the hills.”

West of San Pedro there are hills filled with nice houses from the 1950’s and 60’s. Old money. The area is called Rancho Palos Verdes. Why she didn’t just tell me that, I don’t know. I suspected I was not the first cab driver to endure a Sunday with her.

“Turn here,” she said. We began meandering through hilly roads that were once considered “the country” in southern California. Asking for the address was now pointless; I wasn’t going to take the time to find it in my Thomas Guide (a map book with microscopic street names). Besides, most houses were set back behind trees. I had to trust her.

Higher we went, past horse stables, past ranch style homes and ultra-modern, flat-roofed Bauhaus imitations.

“Here, turn in here.”

I could see no house. The drive went along the side of a hill lined with uncoiffed vegetation taller than me. Oak limbs hung low, dry leaves formed speed bumps across the drive, and piles of pine needles had gathered where the wind left them. I stopped at a set of modern, floating stairs. The impressive house above me was not a mansion, but certainly designed by an architect who admired Frank Lloyd Wright. All of the outside walls were glass. A flat roof in the Prairie style still shaded better times. The house looked tired, smudgy, shaken, not stirred. I knew there would be no man inside… or anyone else for that matter.

She sensed this was a moment of worry for me.“The check will clear, I promise,” she said, “Besides, you know where I live now.”

I remember it was a good fare for those days, about $35. But would I drive my cab all the way to Rancho Palos Verdes over a bounced check? Would she come to the door? Would she even be alive? And if she was, would she remember me? A sunk cost; I would never return.

“Please come inside while I write you that check.” She was sobering up, sensing my worry, and guessed what I was thinking: she might walk into that house and never come out. Inviting me in was the smart play, perhaps one she had used before. She didn’t open the car’s door until I opened mine.

I walked up the leafy steps behind her, wincing from the odor which still curled away the layers of sweatshirts. At a pebbled glass door, she dug deep under her chin and pulled out a single key on a lanyard. This lady was a professional drunk. She did her drinking far away, over-dressed and unattractive knowing in advance she would pass out in the bushes, or in an alley, bereft of cash and dignity, yet with that house key safely around her neck. It was her deliverance. Whatever happened, she would have that key.

When she opened the door, I walked into 1959. The modernist home was not large, probably less than 2000 square feet, but is seemed much bigger, with the main living area and kitchen separated by partial walls; no doors, glass all around and an acoustic ceiling. The far glass wall of the living room faced south and framed a verdant valley dotted with houses of various eras. A baby grand piano filled one corner, its ebony surface dulled with dust and sheet music was scattered below on a huge Persian rug. A liquor cart with a Manhattan skyline of booze was parked at one of the few non-glass walls. The bottles looked unopened. Every vertical surface that wasn’t glass was covered with photos expertly framed and placed by a proto-Tetris savant. Photos of her family in Kodachrome glory: A young mother with long, raven hair and her children. Switzerland, Paris, pyramids, Athens, canoeing, graduations, academic degrees and oil paintings with angular lines and vivid colors, the kind that once blessed jazz albums before Ed Sullivan paid the Liverpudlians. No weddings.

She offered me coffee. No thanks. She offered me tea. No. She offered water. No. That was ungracious of me, unmannerly. She scrounged through a desk drawer for the check book and quickly wrote the check. $50.

“Thank you, ma’am, that is generous of you.”

"I loved you, Atthis, long ago

even when you seemed to me

a small graceless child.

But you hate the very thought of me, Atthis,

And you flutter after Andromeda." ~ Sappho

She removed several of her layers and fell back into an angular, orange leather chair with brass-footed peg legs. I kept my distance from any newly exposed stink. Rays from the late morning sun reflected off her bobbed silver hair and smooth cheeks.

In that moment I was shamed. I was struck that I had never looked at her, not really. I had been so repulsed and revolted by her degradation that I regarded the smell, the vomit, her pathetic cry of pain as her entirety. She was not an old woman at all. In fact, she was no more than 55. Her ethos was one of Peace Corps optimism and Silent Spring activism. She probably went all the way with LBJ but later loved Eugene McCarthy. Her kids watched Mr. Rogers, and she watched Firing Line, but only for the guests, never forgiving Buckley for what he did to Vidal and Baldwin. A born PBS subscriber, ever curious, always chasing culture, Unitarian in sentiment if not in faith and Emersonian to the core. She believed in herself, wore little make-up, never dyed her hair and tried to eat right. And yet none of it gave her the buoyancy to float atop the booze. Instead she sank, or was forced under by persons or tragedies.

She lifted a glass of water, Waterford crystal I recall, elegantly to her lips and swallowed, tilting her head to the sun, eyes closed, as all the night’s poisons burned away. She coughed slightly and then spoke, her once gravelly voice now a clear alto.

“I know I have put you through some trouble. I am sorry. The check will clear, I promise. You are a student, aren’t you?”

“Yes, ma’am, journalism major.”

“Well, I have a terrific library, please take anything you like. I mean it, help yourself.”

I love books and I felt ashamed at having refused her earlier offer of refreshment, so I agreed. The several enormous book cases in a cove to the side of living room and were as tall as the ceiling, about 9 feet. Hundreds of volumes. Most seemed incredibly arcane to me then. I remember she did have the Great Books Collection. She sensed my perplexity and overawe.

“What has been your favorite course so far?”

“My classics course.”

“Ah, so you have read Homer? What else?”

“Some Plato, the Stoics, the Lysistrata, Jason and the Argonauts and the plays of Plautus.”

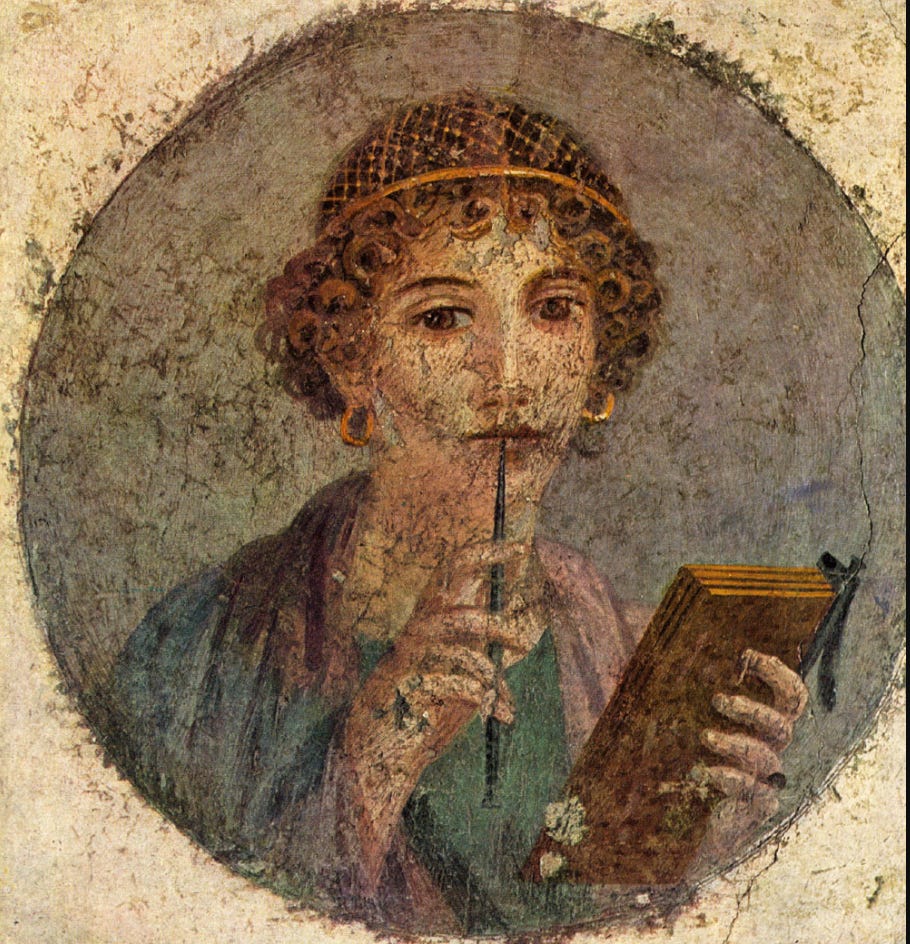

“What about Sappho?”

I didn’t know Sappho. Prideful youth that I was, I didn’t admit this.

“We weren’t assigned Sappho.”

She hopped up from her chair. “Oh, you must read Sappho. If you read Homer you must read Sappho.”

I held my breath as she walked past, but the smell had dissipated. She knew just where to look.

“I want you to have this,” she said, looking into my eyes for the first time. She had baby blue eyes, now clear and hopeful. “Sappho was a great poetess who loved all things sensual.”

The book was a small, hard-bound volume with a grey cloth cover published before the days of dust jackets. This seemed gift enough for me, remembering my empty cab in the leafy driveway; every minute I was not in Long Beach was a minute without a fare. “Thank you, ma’am. I will enjoy it.”

“You will. Sappho loved men, strong men, and maybe a few girls, but she was not a lesbian, that is a lie, you know.”

I left her at her door; for some reason she showed me out, like I was a guest. I turned back and thanked her again for the book. Behind her I saw that skyline of bottles in the liquor cart glinting in the sun. Her self-destruction was not yet house bound, but it would be eventually. I felt guilty walking down those concrete steps, like I had only enabled her to ruin herself again the next week. Who was I to intervene, though? I was just a cab driver. I should have prayed with her or for her, but I was an atheist then, a libertine and nihilist in my own right, incapable of understanding that pangs of shame and guilt come from the Holy Spirit tugging at one’s elbow.

I took the little book home and read only bits here and there over the years. I recently gave it to a friend; a book unread is kind of crime to me now, like owning dog which never gets a scratch or a loving pat.

"There is no place for grief in a house which serves the Muse." ~ Sappho

*Flag drop: named for a mechanical device one used on taxis for calculating a fare. A “Flag drop” was the initial charge just for starting out. After that, the fare is based on time and mileage. The flag-drop in Long Beach in 1988 was $1.97; the highest in Southern California.

Great, great story.